This publication was created to inform producers about the legal concepts associated with these issues and offer tools and ways to handle the various situations that may arise. Specifically, it deals with the notion of breaking and entering on private property and potential recourses under both civil and criminal law.

What is defamation?

Generally speaking, defamation consists of the communication of statements or writings that cause someone to lose esteem or consideration or that arouse unfavourable or unpleasant feelings about someone else. Statements may be considered defamatory by virtue of what they express directly or what they insinuate, for example through the use of irony or the association of facts. The assessment of the defamatory nature of targeted statements is made according to an objective standard. Thus, the question must be asked whether an ordinary citizen would consider that the remarks made, taken as a whole, bring the reputation of the targeted person into disrepute. This means that not every critical or unfavourable comment will automatically be deemed defamatory: each case must be examined on its own merits.

What about harassment and intimidation?

The courts define harassment as vexatious conduct characterized by repeated actions, words, or behaviours that are intentionally offensive, contemptuous, or hostile toward a person or persons and that result in detrimental consequences for them..

Harassment is based on behaviour—in the general sense of the term—as opposed to defamation, which has to do with words.

The Dictionnaire de droit québécois et canadien defines intimidation as an offence in which one person—with the intent of illegally forcing another person to do or refrain from doing something—inflicts violence towards another person or their family, damages their property, persists in following them from place to place, or surrounds their home or workplace.

What about freedom of expression?

In Quebec, every person has the right to have his dignity, honour, and reputation safeguarded. These protections are enshrined in the Civil Code of Québec and the Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms.

These rights must, however, be reconciled with the other rights that every person has, including freedom of expression. Thus, the right to freedom of expression must be exercised with respect for the right to protection of reputation, and vice versa. The role of the courts is therefore to strike a balance between these two rights and not to arbitrate matters of courtesy, politeness, or taste.

What purpose does a civil remedy have?

An action for defamation, harassment, or intimidation, may seek to condemn the perpetrator:

- To cease the alleged acts and/or withdraw the defamatory statements;

- To pay a sum of money in the form of compensatory damages and/or punitive damages;

- To publish an apology.

What must be proven to win your case?

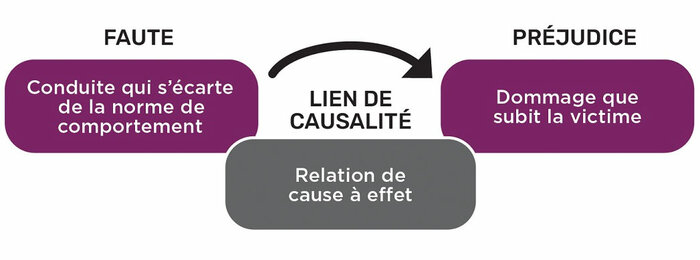

To be successful, the plaintiff must prove fault, damage, and the existence of a causal link between the fault and the alleged damage.

Fault

Fault arises from a behaviour that differs from the standard of behaviour that a reasonable person would adopt. It can, for example, be a malevolent action in which a person, acting consciously and in bad faith or with injurious intent, attacks the victim’s reputation. It may also be a behaviour by which someone damages another’s reputation through negligence, recklessness, or carelessness. Defamation may result if the author makes unfavourable remarks about a person knowing them to be false, or if he makes unfavourable but true remarks about a third party in a slanderous manner and without just cause. Communication of information, whether true or false, may be defamatory.

Damage

This is the harm suffered by the victim. It can be material (loss of income), moral (stress or anxiety), or bodily (physical injury). For a damage to exist, the statement must be deemed defamatory in the eyes of an ordinary citizen.

Causation

The victim must demonstrate a link (i.e., the cause-effect relationship) between the fault committed and the damage suffered.

Limitation period to file a lawsuit

| Defamation | Harassment or intimidation |

|---|---|

One year from the day you find out about the defamatory statement. However, this period is three months if the remarks are published in a newspaper. Regardless of the amount claimed, it is not possible to sue before the Small Claims Division of the Court of Québec. Before the Court of Québec if the amount at stake is less than $85,000.* Before the Superior Court of Québec if the amount at stake is $85,000* or more*. | Three years from the time of the offending behavior. Before the Small Claims Division of the Court of Quebec if the amount at stake is $15,000* or less. Before the Court of Quebec if the amount at stake is less than $85,000*. Before the Superior Court, if the amount at stake is $85,000* or more. |

*These thresholds are subject to change.

How to deal with defamation, harassment, or intimidation?

If you are a victim of defamation, harassment, or intimidation, it is important to keep evidence of the harassment, defamatory statements, or intimidation that has been directed towards you. To this end, it is recommended that you keep a written record of the events. Write down the sequence of events so that you can remind yourself of them at a later time, for your testimony in court, for example. Also, take photos of the elements that may serve as evidence of damages.

You should also:

- Contact your regional federation or your specialized federation to inform them of your situation and seek advice;

- Consult a legal advisor to determine your best options.

Below we provide a non-exhaustive list of actions you may consider to stop the intimidation, defamation, or harassment prior to taking legal action, depending on the particulars of your case. Each situation is accompanied by an example drawn from case law to illustrate how the courts have dealt with a similar issue. Note that very few decisions exist on such matters in the agricultural field.

Defamatory statements on the Web and social media

- Use the «Block» function to prevent the person from viewing your profile;

- After taking screenshots of defamatory comments, report them to the moderators of the web page or social media platform (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, etc.). The moderators may sometimes intervene by removing publications from their platform, or deleting the account of a holder who adopts the denounced conduct;

- Customize your privacy settings to block certain people from accessing information about you;

- Avoid responding to the authors of such statements. They may stop sending such messages if they fail to get a reaction;

- Send a formal notice to the author of these comments to apologize or retract publicly with or without a claim for damages;

- Contact your municipal police service and file a complaint if the comments may be considered violent or endanger your life or safety.

Case law

Skene c. Sanatorium historique Lac-Édouard, 2017 QCCS 5992

A citizen published numerous comments on Facebook and made multiple unfounded complaints to various government authorities against an agricultural producer, for example insinuating that he watered his strawberries with polluted water, exploited foreign workers, and poisoned birds. In this case, the court ruled that Mr. Skene acted maliciously towards the defendant by lying, making insinuations, and causing embarrassment. For having made these defamatory statements, he was ordered to pay $57,932.03 for intentional damages, with interest, and additional indemnity.

http://canlii.ca/t/hpmxh This link will open in a new window

Lapensée-Lafond c. Dallaire, 2014 QCCQ 12943

If the infringement is unlawful and intentional, publishing defamatory and untruthful messages about someone on social media constitutes a dissemination justifying the award of punitive damages under the Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms.

http://canlii.ca/t/gfz82 This link will open in a new window

Defamatory statements on a sign

- Contact your municipality to find out whether such a sign is permitted and complies with municipal by-laws. In the case of an infraction, the municipality may issue a fine and require the removal of the offending sign;

- Send a formal notice to the author of the statement asking for a public apology or retraction, with or without a request for damages.

Case law

Municipalité de Saint-Elzéar c. Marcel Vallée, QCCM Sainte-Marie

A citizen, who was displeased with the sounds and odours coming from his neighbours’ hog farm, was fined and ordered to pay a total of $739 for his protest sign, which was deemed illegal. The sign in question did not comply with the dimensions and distances stipulated in the municipality’s zoning by-law. The court also issued an order allowing the municipality to remove the sign at the owner’s expense if he did not remove it himself within 15 days of the judgment.

Note, however, that the judge did not rule on whether or not the statements on the sign were defamatory. The decision was based solely on the municipal zoning by-law, which specified dimensions for signs on private property.

Defamatory statements in a newspaper or online media

- Send a formal notice to the author of the statement to apologize or retract publicly with or without a claim for damages;

- If the article was published in a newspaper, give the newspaper three days’ prior notice before taking legal action.If the newspaper publishes a full retraction in the issue published on the day or the day following the day of the receipt of notice and justifies its good faith, only the damages in compensation for the prejudice actually suffered may be claimed.Also note that the time limit for bringing an action is three months from the publication of the article or from the knowledge of the publication, provided that in the latter case the action is brought within one year from the day of publication of the article.

Case law

Gélinas c. Savignac, 2004 CanLII 19433 (QC CS)

The remarks “Must citizens who are dealing with a malicious, self-centred, and dishonest farmer always have to resort to the justice system if they want to live in peace in a farming area?” [translation] appeared in an open letter criticizing a producer’s hog farm project. These remarks were not found defamatory. In this case, the court noted that the agricultural producer targeted by these remarks had himself often used “media in an aggressive and sometimes derogatory fashion” [translation] regarding the same project. The court added that “when we vigorously defend a project that we care deeply about, publicly, and often with hurtful words and actions, we must expect that those on the other side will also hurt us sometimes.” [translation]

While the remarks in the following case are not related to the agricultural world, we present them as an example of statements that were deemed defamatory.

http://canlii.ca/t/1gkn6 This link will open in a new window

Blouin c. Limoges, 2010 QCCS 5319

The court held a newspaper and its editor (and sole journalist) liable for publishing material stating that municipal councillors in Sainte-Anne-des-Plaines were “crooks, shabby and unscrupulous politicians, profiteers who abuse public money, elected representatives who engage in favouritism, who belong to the small mafia and who behave like those investigated for sponsorship through the Gomery inquiry.” [translation] For publishing these defamatory remarks, the newspaper and editor were ordered jointly and severally to pay a total of $120,000 in moral damages and $21,000 in punitive damages.

http://canlii.ca/t/2d85d This link will open in a new window

Breaking and entering

The following section outlines more specifically the rights and recourses of producers in the event of illegal entry into their farms by protesters or activists.

Civil law

Protestors or activists who illegally enter farms violate property rights.

The right to property is recognized by article 947 of the Civil Code of Québec and enshrined in the Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms. Section 6 of the Charter stipulates that every person has a right to the peaceful enjoyment of his property.

The Charter also protects other rights that may be infringed upon when a producer suffers an intrusion on his property, namely the right to privacy and the inviolability of his home. Sections 5 and 7 of the Charter state that every person has a right to privacy and that the home is inviolable.

Criminal law

Breaking and entering

Protestors trespassing on a farm may also commit the offence of breaking and entering under section 348 of Canada’s Criminal Code.

The maximum penalty for breaking and entering a premise with intent to commit an offence or actually committing an offence is life imprisonment if the offence is committed in relation to a dwelling-house and 10 years imprisonment if the offence is committed in relation to any other premise. The court may also impose a fine.

While it is recommended that you keep your buildings locked at all times, the criminal offence can be committed whether or not the doors are locked.

Other criminal offences

In the context of a demonstration on a farm, the following offences may also be committed:

- Breaking the peace;

- Mischief (damaging or interfering with the legitimate use of property);

- Participating in an unlawful assembly;

- Concealing one’s identity during an unlawful gathering;

- Disguising oneself with criminal intent;

- Assault;

- Carrying a weapon with dangerous intent;

- Interfering with the work of a peace officer.

Case law

R. c. Krajnc, 2017 ONCJ 281

In this Ontario case, a vegan activist was charged with mischief for giving drinking water to pigs in a truck that was stopped at a red light. The court found the activist not guilty because the Crown did not demonstrate beyond a reasonable doubt that her actions prevented, interrupted, or hindered the legitimate use, enjoyment, or exploitation of property.

http://canlii.ca/t/h3kf9 This link will open in a new window

As in defamation cases, there is very little case law dealing with breaking and entering on farms. The following is a recent decision that illustrates the problems that can be presented to the court in cases of breaking and entering; it also confirms the protestors’ obligation to identify themselves to police.

Marsan c. Ville de Montréal (SPVM), 2019 QCCQ 6327

During a demonstration organized in support of social housing, a crowd of approximately 100 people rushed into the former Viger Hospital. Responding to a call for breaking and entering, the police required the demonstrators identify themselves before leaving the building, considering that they had broken into a private property and there were reasonable grounds for believing that mischief had been committed. Invoking freedom of expression and the fact that they were allegedly detained in a building against their will, the protesters brought an action for damages against the City.

The court dismissed the case, stating that the police officers’ requirement that the protestors identify themselves upon exiting the building was in no way unreasonable and in no way diminished the participants’ right to protest. Furthermore, even though the building doors were open, the protestors knew that it was private property and that they had no right to enter. By going inside the building, the demonstrators committed a break-in.

http://canlii.ca/t/j2z37 This link will open in a new window

Recourses

In the event that protestors break into your farm and cause damage, civil and criminal recourses are possible.

Civil recourses

It is possible to bring a civil liability action against someone who has entered your property without your permission. As in cases of harassment, in order to win, you must prove fault, damage, and causation between the fault and the alleged damage. In this regard, refer to the previous section, What must be proven to win your case?

Such an action may be brought against a particular activist, against several activists, or against the association that represents the group, provided that the group has a separate legal personality. In the latter case, it is wise to make sure that the association has a legal existence in Canada and the funds to honour a judgment that would order it to pay a sum of money.

Recourses under the Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms

When a Charter right is violated, money may be claimed for punitive or exemplary damages in addition to money for damage suffered. The damages may be awarded to a natural person or a corporation, such as a company.

Punitive or exemplary damages are sums that are awarded to the victim as reparations and whose primary objective is to punish the wrongful and reprehensible behaviour of the perpetrator. Their purpose is to prevent and deter undesirable behaviour.

Depending on the circumstances, a producer who suffers damage (material, psychological, or bodily) may claim sums not only for the damages suffered, but also for additional sums in the form of punitive or exemplary damages.

For such damages to be awarded by the court, the offence must be unlawful and intentional. In the case of breaking and entering by activists whose actions appear peaceful, the intent to cause damage may be difficult to prove.

A number of decisions have been rendered on this point, including the following:

Case law

Montréal (Ville de) c. Cipollone, 2014 QCCQ 4917

The court jointly sentenced rioters who caused material damages to pay exemplary damages of $5,000 each in order to set a clear precedent.

http://canlii.ca/t/g8087 This link will open in a new window

Construction Norfor c. Boulianne, 2016 QCCS 1826

The court ruled that breaking a padlock, illegally entering someone else’s property, and performing construction work without permission infringed upon sections 6 and 8 of the Charter, which protect the peaceful enjoyment of property and respect for private property. In addition to ordering the plaintiffs to pay for the damage caused, the court ordered them to pay $3,000 in punitive damages to punish their wrongful, malicious, and intentional conduct.

http://canlii.ca/t/gpn18 This link will open in a new window

Criminal and penal recourses

The judicial process for criminal matters is somewhat different from the civil process. With the exception of the extremely rare case of a private complaint (very exceptionally, a citizen may file a criminal complaint himself or herself), criminal and penal accusations are laid by a criminal and penal prosecutor. This prosecutor assesses whether the evidence collected is sufficient to lay charges, and it is up to this person to determine which charges, if any, are laid. If the prosecutor decides the evidence is insufficient, he may close the case or call for further investigation.

If the producer has reasonable grounds to fear that activists will reenter his property, endanger his life or the lives of his family, or damage his property, he may seek an order from the court that the persons concerned enter into a peace bond. Depending on the circumstances, this agreement may state that the concerned parties must refrain from disturbing the public order and conduct themselves properly, prohibit them from being within a certain radius of the producers’ property, prohibit them from communicating with or approaching the producer or the producer’s family, prohibit them from carrying weapons, and so on.

Case Law

R. c. McQueen, 2022 QCCQ 2801.

Eleven anti-speciesist activists who staged a sit-in at a hog farm were convicted of breaking and entering causing mischief and obstructing a police officer. The court did not accept their freedom of expression defence (they claimed that entering the hog farm was the only way they could show and expose the conditions in which the animals were raised) and held that the co-accused could have made their case in a public place.

Activists on farms: How to handle them?

If activists come onto your property:

- Calmly but firmly ask the spokesperson or leader of the group to leave your property, specifically by invoking the right to private property and biosecurity rules;

- Call 911 to have the police service intervene if the activists refuse to comply, if they threaten your safety or that of your employees, or if they damage your property;

- Call the UPA network at 1-888-285-4976;

- Take photos and videos;

- Take notes to remind yourself of the sequence of events.

If a protest is taking place on a public roadway in front of your property:

- Call the police if the protest impairs traffic or endangers your safety or that of public roadway users;

- Request that the police service monitor the situation on the scheduled date, if it is known.

Preventing cases of breaking and entering: |

Defamation, harassment, and intimidation in agriculture

Activists on farms: how to handle them

These guides are intended as a reference tool for farm and forestry producers regarding defamation and harassment in agriculture. They do not constitute an opinion, advice or legal advice.

If you have questions, please contact the UPA’s Legal department by calling 450 679-0251.